How much trouble is Speaker Johnson in?

Johnson is likely to survive this Congress, but the speakership is not the secure position it once was.

Just more lies from the Speaker.

- Rep. Elise Stefanik (R-NY), on X

I certainly think that the current leadership and specifically the Speaker needs to change the way that he approaches the job.

- Rep. Kevin Kiley (R-CA) in the Washington Post

[Your job is] slipping away…morale has never been lower.

- Anonymous lawmaker to Speaker Johnson, as quoted on CNN

These recent quotes from House Republicans suggest that Speaker Mike Johnson faces deep unhappiness with, if not outright hostility to, his leadership among the GOP rank-and-file.

Some reporters and commentators have taken this as a sign that Johnson is in danger of losing control of the chamber or even being ousted from speakership entirely. (See for example here, here, and here.) Rep. Elise Stefanik suggested in an interview that Johnson was all but finished as speaker, though she later walked that back.

While lawmakers’ grievances with their leadership should not be ignored, I am skeptical that Johnson’s immediate future as speaker is in danger. At the same time, it’s worth noting that the larger political environment is a treacherous one for Johnson. Indeed, he is but the latest speaker to serve at a time when the speakership offers far less job security than it once did.

Republican grievances against Johnson

Why are House Republicans so unhappy with Johnson? A number of complaints have bubbled up over the past couple of weeks. They include claims that Johnson is:

endangering lawmakers’ reelection by not bringing bills to the floor that address voter concerns, such as higher prices and rising health care costs.

supporting Trump’s demand for mid-decade redistricting, even though it has created a tit-for-tat dynamic that endangers Republican incumbents in Democratic states (a major reason for Congressman Kiley’s unhappiness with Johnson).

using his agenda-setting power to block bills desired by individual lawmakers (see for example here and here).

not helping Republican legislators get their provisions into bills (Stefanik’s specific gripe).

refusing to convene the House during the government shutdown, keeping lawmakers from doing any legislative work.

surrendering the power of the House to Trump, giving lawmakers little to do. As a result, as Tom Massie (R-KY) opined, “You could get a monkey to do this job.”

pleading ignorance as an excuse to not serve members. (This was Stefaniks’ complaint, which may or may not be true – though Johnson does use that tactic to avoid defending Trump, a move that has been rightly ridiculed.)

This a long list, but more troubling is that they touch upon central goals of lawmakers, including reelection (the first two complaints), making policy (the third, fourth, and fifth), and influence (the sixth). As Doug Harris and I have shown, when choosing party leaders, lawmakers weigh heavily whether candidates will satisfy those goals. An incumbent leader’s failure to do so can thus generate a dangerous amount of dissatisfaction.

However, I am skeptical that these gripes are an indication that Johnson is about to be removed by his own party. For one thing, some lawmakers who are complaining publicly may be motivated more by politics than by genuine unhappiness. Speakers are expected to serve as a verbal punching bag for lawmakers who want to distance themselves from party leadership, so by being a scapegoat and suffering these rhetorical slings and arrows, Johnson might actually be helping the rank-and-file politically.

Even if these critiques are genuine, Johnson has the House’s rules on his side, which were modified this year to prevent a single lawmaker from forcing a vote to remove the speaker (in response to what happened to Kevin McCarthy in 2023). Also in Johnson’s corner is President Trump, who still has tremendous sway over his party, though he hasn’t always been very helpful to Johnson.1

Finally, few if any Republicans want the job – for good reasons, as I’ve documented elsewhere. (GOP speakers especially face major headwinds when trying to lead the chamber, as I’ve explained elsewhere.) As Tim Burchett (R-TN) asked rhetorically, if there were an effort to kick Johnson out, “Who’s going to replace him? Who can get the votes?”

Johnson himself has acknowledged that the job is not much fun. In a surprisingly frank podcast interview that he and his wife recently did with Katie Miller, Speaker Johnson complained about his unending workload, fielding late night calls from needy lawmakers (and their “drama,” as he diplomatically put it), and an ever-present security detail. (I highly recommend watching the whole thing, if only to get a glimpse into Johnson’s personality and humor.)2

Most contemporary House speakers do not last long

Johnson may not be in immediate danger of removal, but that doesn’t mean his job is 100% safe. His miniscule majority means that just a handful of GOP resignations could cost his party the majority. Marjorie Taylor Greene has already announced she is leaving Congress next month, and two others, Nancy Mace (R-SC), and Don Bacon (R-NE), have reportedly considered quitting in recent weeks.

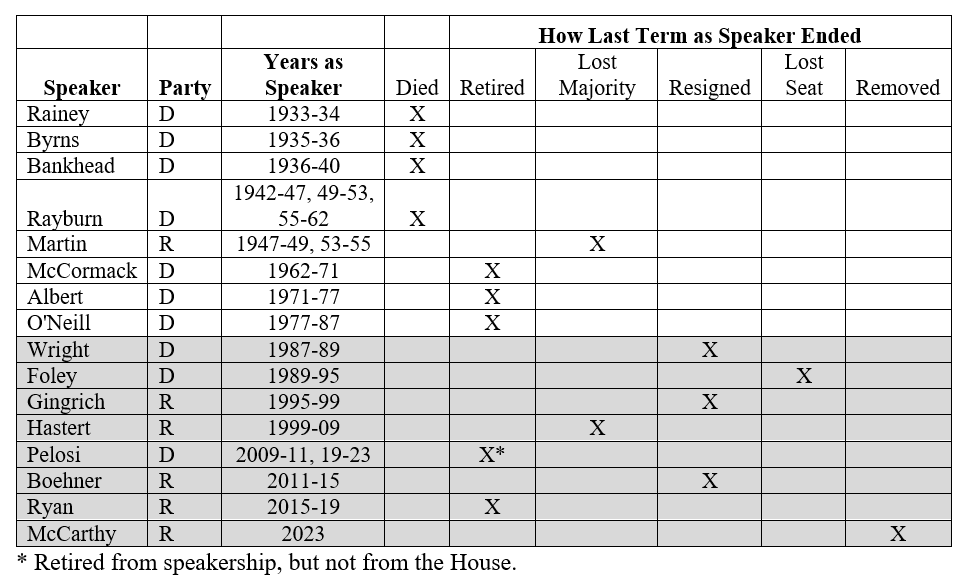

More generally, Johnson is speaker at a time when the job is no longer the secure post it once was. The table below (an update of one I did in 2015) shows how each speaker since 1933 ended their tenure in leadership.

Until the mid-1980s (the non-shaded portion of the table), almost all speakers stayed in office until they died or retired. That is no longer the case. While Pelosi and Ryan ended their careers by retiring from the post (and, in Ryan’s case, also retiring from Congress), the most common means of ending one’s term since 1987 has been to resign in the middle of one’s term (Wright, Gingrich, and Boehner), something that was once unheard of. Other speakers existed the job by losing reelection (Foley), when their party lost its majority in an election (Hastert), or by being removed by the House (McCarthy).

There are many reasons for this increased job insecurity, including narrower majorities in the House, more frequent changes in party control of the chamber, and the rise of intraparty factions that seek to undermine the incumbent speaker. One of my recent graduate students, Kristen Morrow, found in her dissertation that the speakership has become a more popular target of public criticism, which may contribute to the decline in public standing of speakers, making them more politically vulnerable.

Johnson faces all of these challenges. Not only is his majority a tiny one, but it has at least one intraparty faction (the House Freedom Caucus) with a history of being poor team players, and it is likely to shrink to a minority after next year’s elections. And as with past speakers, criticism of Johnson in the public sphere has been relentless, undoubtedly helping depress his popularity ratings.

So even if Johnson can somehow quiet his critics in the GOP Conference (as he is apparently trying to do), by no means can he count on keeping the job very long.

In addition to forcing Johnson to repeatedly defend his illegal or unconstitutional acts, Trump pardoned a Democratic lawmaker facing a tough reelection – without warning Johnson – and has privately joked that he, not Johnson, is the real House speaker.

Not that one should have too much sympathy for Johnson, who wanted the job, after all – and, according to a recent book by Annie Karni and Luke Broadwater, may have been angling for it for some time.